- Home

- Jablonsky, William

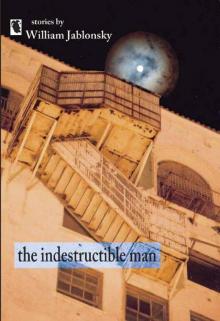

The Indestructible Man Page 8

The Indestructible Man Read online

Page 8

“Uh, Jeff?” I’m a little nervous, because it’s not every day somebody grabs your head. “What are you doing?”

He stares at me, then takes his hands off me. He gives me one of those looks, the way your dad looks at you once all the things he hoped for you have gone down the drain. It makes me ashamed, and I want to run out of there and never come back.

“I’m sorry.” He grabs a tissue and wipes off his hand like he’s getting rid of the filth.

“You are out of your goddamn mind,” I say, and head for the door.

It’s Saturday night and I’m bored. Allison’s not home and I have a pretty good idea where she is. I’d usually call Jeff at a time like this, but he and I aren’t going to be talking for a while. So I go to Yukon Eric’s by myself, thinking maybe I’ll run into somebody there.

I still feel Jeff’s handprints on my head even after washing my hair. I muss it a few times, but it doesn’t help. Worse yet, I keep thinking it’s my fault that what Jeff did to me didn’t work.

When I get there Jeff’s in a booth with Allison and Mike, and Roger, and a couple of people I’ve never seen before, all gathered round a table listening to him. Allison spots me, but she turns right back to Jeff. I do my best to stay out of sight while I put away my first beer and try not to notice the dirt and grease on the mug, the dust on the bar, the popcorn and paper scraps on the floor.

After I finish my second I see Jeff and his crew getting up. But the guy who got in my face last night is there too, with three or four friends. He looks pissed. The guy stands in front of Jeff, blocking his way so he can’t leave. Jeff puts his hand on his chest like he did before, and it looks like he owns him all over again. But one of the guy’s friends comes up from behind and jabs Jeff in the ribs with a pool cue. Mike tries to step between them, but gets shoved across the room. Next thing I know Jeff’s on the dirty, scummy floor and the guy and his friends are kicking his ribs in. He doesn’t scream or try to get up; he just lies there and takes it.

Allison grabs my arm. “Jesus, what’s wrong with you? Help him!”

I get up, and I’ve got a cue in hand, and in about ten seconds I could drop every one of them. But I don’t. I just stand there looking down at Jeff on the filthy floor.

Finally the asshole and his friends decide he’s had enough, and when the crowd parts I see Jeff on his hands and knees, face covered with blood and grime, looking past me with eyes so wide and white I’m actually scared of him.

Mike and Allison and the rest swarm around him, lift him up and haul him out the door. I try to catch a glimpse of him as they carry him away through the dark, but he’s lost among them. I should follow them, make sure Jeff’s all right, but when I close my eyes all I can see are his taillights racing up the road, tires trailing dust for a mile back, and me chasing after him, so far behind I know I’ll never catch him.

For Safety’s Sake

Because our eight-year-old son Jacob believes he can fly, we have taken extra precautions around the house. We smashed our ladders to splinters and removed the gutters from the outer walls, and cut down all the climbable trees in the yard, leaving only the spindly red maple Dora planted just after our wedding, when we first moved in. We even installed a steel mesh fence between the upstairs railing and the ceiling to prevent him from vaulting over the side; Dora found it particularly hard to watch the contractors drill holes in her honey-stained oak banister. We forbid him to go near steep hills or embankments, to swing too high on the playground, to climb to the top of slides or monkey bars. Neither Jacob nor his brother Ferlin, who imitates his every move, is to climb any structure more than five feet off the ground, under threat of grounding. We watch Jacob as long as we are able, and frequently call his friends’ parents to make certain they know our wishes. Sometimes Dora threatens to relent, insists what we are doing to Jacob is too restrictive and will give him a complex. But she understands it is for the best.

Jacob has absolute faith in his power, literally believes he can catch air currents under his outstretched arms, lift his feet from the ground, and rise into the air. It only takes a jump from a high place or a good steady sprint, he claims, and with a bit of will he is airborne, flying up to a hundred feet at a time before hitting the ground in a light jog. He admits he has not yet mastered landings, and while perfecting his skills he sometimes incurs crusty scabs and purple plum-sized bruises on his knees. He has been at it for months, he says, going farther and farther each time, and someday soon he will be able to soar indefinitely.

He has even won over some of the other neighborhood children, who openly claim to have seen him leave the ground. Dora and I try to discourage him, change the subject if he starts to re-enact his experiences for us at dinner. We have confined him to the house more than once to stop him from jumping off some nearby bridge and drowning.

Ferlin is six and believes he will one day follow Jacob into the air. Again and again we tell him it is impossible, but I do not doubt that, when we are out of earshot, Jacob feeds his imagination and his faith, promising Ferlin he will fly. Often I see the two in the empty lot behind the house: Ferlin running across the crabgrass, head down, arms outstretched and angled behind him like fighter wings. His brother waves him on, encourages him to run faster, laughs as Ferlin thrusts upward with his chubby legs, trying to hurry his flight. He leaves the ground for less than a second at a time, then his feet cross and he tumbles end over end. Each time he falls Jacob helps him up and urges him to try again, as many times as it takes.

I consult encyclopedias and science textbooks, give them Popsicles and sit them on the couch, and explain the principles of gravity, the differences between human and bird anatomy, why we are confined to the ground and they are not. Ferlin at first accepts what Dora and I tell him and bears his re-education with a shrug and a sigh. Jacob listens politely, then scrunches his brow and shakes his head in disbelief, certain I lack the faith and wisdom and imagination to believe him. When reason fails I try intimidation, make my position clear: human beings simply cannot will themselves into the air. I loom over him each night before bed and order him to say, “Only birds and airplanes can fly,” looking into his eyes for the proper sincerity. He is to repeat the chant nightly until I am satisfied he believes it. He is not to contradict me afterwards, nor remind me of other flying animals such as bats or insects. He stares at me with a tiny smirk as he recites, a quiet signal that I will never break him, that his version of the truth will ultimately win Ferlin back.

Because we fear his delusions might lead Ferlin to injury, we take Jacob to as many therapists as we can afford. All claim there is nothing wrong with him—he is simply an intelligent, imaginative child. What they fail to grasp, and do not wish us to explain, is that it has never occurred to Jacob that he might be wrong. His teachers tell us he is a bright boy, reasonably well-liked, with no significant difficulties; he is not bored, unchallenged, or wanting for attention. Other than believing he can fly, which the doctors tell us will pass, Jacob is perfectly normal. Still, we feel he is too old for these childish fantasies, and try to quash them. To keep away temptation we forbid him to read super-hero comics or fantasy stories—we view Superman and Peter Pan as bitter enemies, and do not speak of them in our home. I consider boarding up the windows or installing blinds with locks only Dora and I can open to prevent him from being inspired by the birds outside. Dora insists it is too extreme, but she promises to keep an open mind in case the situation should worsen.

Despite our precautions I still find evidence of Jacob’s daredeviling—a few noticeably bent branches at the very top of the red maple, dusty footprints on the roof beginning a few feet from the edge and leading to the thatched crest. The thought of him hanging from those flimsy limbs keeps us awake nights. So one Friday afternoon after school I dig up the chainsaw and force Jacob to sit with Dora on the front porch and watch the saw spit sawdust and chunks of maple bark, so he can see the cost of his persistence. Dora sits quietly, eyes closed against the dust, and does

not speak. She sleeps in the guest bedroom for three nights, but creeps quietly back on the fourth. She knows sacrifices must be made for our children’s safety, and we speak no more of it.

Still, every few days new clusters of bruises appear on his shins and knees, probably from falling on the gravel playground at school. I call his teacher and ask her to keep a closer watch on him, though she insists she is not responsible for playground supervision and knows nothing of Jacob’s recess activities. I urge her to take her duties more seriously, and threaten to contact Principal Greenberg. She, in turn, asks that I stop telling her how to do her job. Furthermore, she says, Dr. Greenberg is well aware of our complaints and no longer finds them amusing. I hang up angrily; Dora begins researching alternative schools where Jacob’s behavior might be more closely monitored.

The next morning I take an extended lunch hour from the bank to watch him on the school playground. I park the station wagon behind the old farmer’s market, a collapsing shack with chipping green paint across the street from the school building. It is the perfect cover, out of sight of the classrooms and even the tallest playground slide, which rises silver-gray far above the swing sets and jungle gyms. I crane my neck around the splintered corner and watch Jacob climb to the top, hold his arms in front of him like a high-diver, and launch himself into space. For a moment he seems to hang in place, his legs treading the air like water, then he descends slowly, like down falling from a bird’s nest. I close my eyes; daydreaming and too much coffee on an empty stomach have brought on hallucinations. When I open them again Jacob is on the ground, stomping through the gravel with his friends. I laugh at my delusion and sneak back to the car, formulating Jacob’s punishment and idling quietly until the warning bell rings and the double doors suck the long lines of children back inside.

As a result Dora and I allow him to play outdoors only under our supervision, and before I let him sleep I make him swear on his grandmother’s grave he will stop trying to fly. Later, when I believe he is asleep, I quietly open his door. In the sliver of hall light I see him staring at me, his upper lip curled into a snarl, hands folded over his chest and clenched tightly, the knuckles forming small sharp peaks.

In the morning he glares at me silently over his oatmeal, his mouth curled into a subtle, defiant smile. His eyes seem to say, You will never beat me.

I begin standing out on the sidewalk, blocking the paths of bicycles, hoping to intercept Jacob’s friends, any neighborhood children I recognize. I offer five dollars to any child who will tell me whether Jacob is still bent on flying, or show me the secret places where he practices. Dora refuses to take part, insisting this is too much, she cannot betray her son, cannot even watch. But when I return five dollars poorer she is eager enough to hear the information I have bought.

Some children are greedy enough to comply, naming all the times and places Jacob puts on his exhibitions: in the church parking lot near the school before the warning bell; behind the basketball courts during morning recess; after school, behind the wall of spruces that separates the playground from the empty field. To avoid suspicion he and Ferlin have been catching rides home from other children’s parents. They cannot provide names, though I offer to double the reward. Either they intentionally mislead me or Jacob and his friends are using them as a diversion; I leave the bank early, arrive at the prescribed time and place, but there is no Jacob, no Ferlin, only children playing half-court basketball or Red Rover.

Most of Jacob’s friends shake their heads and politely decline, unwilling to betray him. Some tell their parents, who call us angrily and accuse me of harassing their children. Dora feigns ignorance: there must be some misunderstanding, she tells them, nothing to worry about, nothing at all.

One afternoon, when school is out and Jacob is safely shut away in his room, I look out the window and glimpse a blonde girl about his age pedaling her pink Schwinn down the sidewalk—Marla, the Klaupmanns’ youngest daughter, Jacob’s friend. She does not speed away when I cross the lawn; she knows me, knows my offer. She skids to a stop and sighs, shakes her head sadly.

I give her my friendliest smile, kneel so we are eye to eye. “You’re friends with Jacob, right?”

“My mom said not to talk to you.”

“I know. I just want someone to tell me if he’s still trying to fly. And where he does it. I’m afraid he’s going to get himself or his brother hurt very badly.”

I begin to pull the five-dollar bill from my wallet, but she rolls her eyes under her curly bangs. “You never give up,” she says. “He can do it, you know. He’s come really close.”

“Is that right?”

“You wouldn’t be mad if you saw. I’ll tell you where if you promise not to punish him.”

I nod and put my wallet back. “Fair enough.”

She raises one eyebrow, gauging my honesty. “Behind the church, after school. Then you’ll see. And remember, you promised.” She slides back onto the seat and pumps the white plastic pedals, streamers trailing from the handlebars as she speeds away.

The next day I again hide the station wagon behind the farmer’s market and idle until the final bell rings. Dora sits beside me, resting her head in her palm and rubbing her right ear, sore from arguing with Deborah Klaupmann over the phone all evening. It has taken some convincing for her to come, but I promise her this is the last time. This time we will end Jacob’s delusions, we will make sure his feet remain firmly in contact with the ground.

Just after three we hear children shoving and hollering their way out the lunchroom doors. We run across the street and inch toward the playground along the outer wall, its weathered brick staining our palms and sleeves chalky-brown.

We peer around the ancient corner, careful to avoid being seen, until Dora spots Jacob in the field near the church, along with ten or fifteen other children gathering to watch. Ferlin jumps up and down trying to get a better view, his pudgy belly jiggling. Jacob scans his surroundings carefully, looks toward the lunchroom doors, the farmer’s market. We duck behind the corner before he spots us.

Jacob takes his place at the foot of the human runway. He takes a deep breath and breaks into a jog for about twenty feet, slowly building to a full sprint. At the limit of his speed, when his feet nearly hit his backside, he holds his arms out, tucks his head between his shoulders, and jumps, the sod seeming to recoil under his sneakers like a trampoline. He hangs in the air for a second or two before his feet touch the ground, the impact tossing up bits of grass. For a moment we smile, chuckle to ourselves: he is only pretending, we have nothing to fear.

Then he leaps again, hangs above the ground, arms outstretched, legs treading empty air like a cartoon character about to fall off a cliff. I feel my overworked deodorant wafting up from beneath my collar. I close my eyes against the afternoon sun; when I open them, I tell myself, his feet will be on the ground, he will not be in the air, he was never in the air at all. But when my eyelids part he is still suspended, as if hanging by wires. Dora and I exchange a quick glance; her expression suggests we ought to slink back to the car and go home and dismiss what we have seen as a mirage, a trick of the imagination. But my legs are numb and tingly and refuse to carry me back.

The other children cheer as Jacob touches ground and leaps again, rising even higher. With each new act of defiance a pressure wells up in my stomach and chest, and before Dora can stop me my numb legs erupt into a run across the playground, my shoes disappearing in gravel with each step.

Not far behind I hear Dora’s pumps clattering on the pavement, Dora huffing as she tries to keep pace. A few children notice me; some shout a warning to Jacob, but he does not seem to hear. Ferlin screams and runs toward me, trying to block my path, but he is too slow and can only follow far behind. The gravelly scrunch under my feet gives way to soft, even sod. Jacob runs faster, arms at his sides, the wind or the children’s hollering keeping him from noticing me. He closes his eyes and takes a final leap; his legs catapult him off the ground like a broad jumper

, his knees bend underneath him, and he glides through open air, disappearing for a moment into the afternoon sun. Dora gasps behind me and stops in her tracks. “You saw!” Ferlin screams again and again, until he stumbles and hits the ground face-first with a soft thud. I keep running, ignore my cramping thighs, shield my eyes against the glare as Jacob rises higher, until all I can see are his red-and-white sneakers coasting at eye level, just out of reach.

When Jacob finally turns his head and sees me, his eyes go wide and his mouth falls open. Still rising, he slows, and his gaping mouth curls into a broad, triumphant smile—now I understand, he knew I would, I only needed to see for myself. With the last bit of strength in my legs I jump, snatch Jacob’s ankle with both hands and hold on tight. For a few seconds my feet find no traction and I begin to coast along with him, until I dig my heels into the thick grass and pull hard, tilting him earthward like a plummeting kite, wrestling him to the safety of solid ground.

The Indestructible Man

The Indestructible Man