- Home

- Jablonsky, William

The Indestructible Man

The Indestructible Man Read online

the indestructible man

William Jablonsky

Livingston Press

University of West Alabama

Copyright © 2005 William Jablonsky

All rights reserved, including electronic text

ISBN 1-931982-47-3 library binding

ISBN 1-931982-48-1, trade paper

Library of Congress Control Number 2004115563

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America,

Publishers Graphics

Hardcover binding by: Heckman Bindery

Livingston Press, Livingston, AL

Typesetting and page layout: Gina Montarsi & David Smith

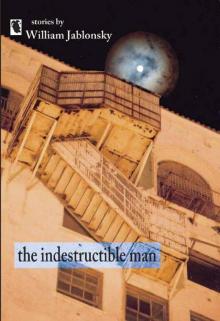

Cover design: Gina Montarsi

Cover photo: Beaux Boudreaux

Author photo: Coral Smart

Proofreading: Chris Hawkins, Ariane Godfrey

Acknowledgements:

I would like to express my deep gratitude to Wendell Mayo for his guidance in the completion of this collection, and to Coral Smart, for her invaluable editorial assistance and moral support.

The following stories have been previously published,

some in slightly different form:

“Dirt and Shit” in Artful Dodge

“The Edge of Solid Ground” in Beloit Fiction Journal

“The Space Between Earth And Moon” in The MacGuffin

“For Safety’s Sake” in Sulphur River Literary Review

“Mary Magdalene Talks To The Street Sweeper” in The Bitter Oleander

“Smoke And Mirrors” in RE:AL

“To The Sleeper” in Eureka Literary Magazine

This is a work of fiction.

You know the rest: any resemblance

to persons living or dead is coincidental.

Livingston Press is part of The University of West Alabama,

and thereby has non-profit status.

Donations are tax-deductible:

brothers and sisters, we need ’em.

first edition

6 5 4 3 3 2 1

Table of Contents

Indestructible Man 1

Saving Joe Deavers 42

Dirt and Shit 52

For Safety’s Sake 61

Little Green Men 68

The Space Between Earth and Moon 82

Seven 94

The Edge of Solid Ground 99

Schoolteacher, 30, Travels Time To Foil Murders 103

A Fear of Falling 112

Mary Magdalene Talks to the Street Sweeper 124

Smoke and Mirrors 128

To The Sleeper 133

the indestructible man

To Coral,

My first and best editor

The Indestructible Man

1

The day Bobby Mercer discovered Romulus Wayne was indestructible was the blackest moment of his life. He had suspected since third grade, when he kicked Romulus down a flight of stairs and watched him walk away without a single bruise. But until that day in August, just before the start of eighth grade, he was never certain.

The incident started when Romulus crossed Bobby’s path skating down a neighborhood sidewalk. Unable to resist the temptation, Bobby stuck out his leg as Romulus passed and sent him tumbling into the overgrown ditch in Mrs. Hulman’s front yard. He laughed as Romulus untangled himself from the weedy mess—Bobby never tired of making a fool of him—and started to skate away. He had gone only a few feet when Romulus’ voice echoed behind him, “Nice try, fatass!” Romulus raised his middle finger high above his head and fled down the sidewalk at top speed. Bobby could not let the insult pass without punishment; he pivoted on his own skates and set after him, planning to rub Romulus’ face in the nearest pile of dog shit.

He chased Romulus for three blocks, drawing near a group of girls running through a jetting lawn sprinkler. At the center, half-hidden from Bobby’s view, was Abigail Wheat, in a yellow and purple striped swimsuit and cutoff shorts, her strawberry-blonde hair dangling down her back and clinging to her damp shoulder. Bobby lagged behind, unable to look away. Romulus was staring too, his neck craned to watch her as he skated past; though Bobby was not yet sure why, he knew Romulus would have to suffer for it.

He never got the chance; Romulus rolled through the stop sign at the corner and into the path of a green station wagon.

The next few minutes were seared into Bobby’s memory: the wagon’s sustained honk; Abigail’s whistling scream as the front bumper struck Romulus in the side; Romulus’ skates clacking across asphalt and gravel, knees and ankles twisting in unnatural directions until his body hit an old maple tree, wrapping around the trunk like a twist-tie.

Bobby considered fleeing as the driver, a woman with a poofed-up black beehive and huge bouncing breasts, jumped out of her car to check on Romulus. She poked a maroon fingernail into Romulus’ shoulder; when he did not move or speak she began to tremble, her purple muumuu quaking with her. Abigail crept up to the contorted body and gently touched his arm, then drew back in terror and began to cry. Mustering his courage and nobility, Bobby took her hand, and when Abigail squeezed it back a warm wave washed through him, a contentment he had never known before.

Then Romulus stirred and groaned, began to sort out his mangled joints. He seemed bewildered, eyes glazed over, his skin a translucent white. As he raised himself on his bent skate wheels, Abigail jerked her hand away and ran to him. A cry of protest gurgled in Bobby’s throat as she smothered Romulus with kisses.

Romulus slowly backed away from the crowd. He felt his ribs and cracked his back—drawing a shriek or two from the girls—and, certain he was unharmed, the shock and fear left his face, his eyes narrowed, and the left corner of his mouth curled into a smug grin. He kicked off his damaged skates and slung them over his shoulder, and winked at Abigail. She covered her red lips and giggled as Romulus walked away in his gray tube socks.

Bobby turned and skated home as fast as his stocky legs could drive him. He felt a hard jagged lump at the base of his throat, and an emptiness in his chest and stomach, as though his torso had been hollowed out with an ice-cream scoop. The pain was worse than any punch he had ever taken, and he was sure it would never end.

2

Romulus Wayne was neither strong, nor good in a fight; his arms were thin and wiry, his blows pinpricks at best. Because of this, because of Abigail, and because his name was Romulus, Bobby felt an overpowering urge to harass him. Romulus seemed an easy target, but bullying him was a challenge. Romulus blatantly refused to surrender lunch money or be coerced into telling gathered crowds he was in love with the janitor, Mrs. Greeley, who had a dark mustache. Bobby could knock Romulus to the ground in seconds, his knuckles smacking deliciously into Romulus’ jaw and cheekbone. But Romulus always picked himself up immediately as if nothing had happened, the left side of his mouth curling into that familiar, cocky smirk. After two or three more knockdowns, Bobby would retreat, rubbing his bruised knuckles, chanting Rom-u-lu-us and looking to Abigail for some faint sign of approval. But as Romulus walked away with his usual nod and wink, her eyes were only on him.

By the eighth grade Bobby knew he was in love with her. Whenever he saw them together he yearned to punch something, more than once driving his fist through the drywall in the boys’ restroom.

Though he often bragged about making quick work of Romulus, Bobby knew he could never truly win. He lay in bed fantasizing about finding Romulus’ weak spot, making him crawl away blubbering. Then Abigail would see Romulus for the smug little bastard he was and admit she had been wrong. He would forgive her, of course, show her he could overlook her error in judgment. He imagined this moment until the warm wave returned, then quietly slid his hand under the wa

istband of his boxers to complete its rushed and fleeting ritual.

That spring Romulus Wayne finally crossed the line. Bobby could barely stand the arrogant sneer, the smiles and winks he shared with Abigail. But when he began to make a spectacle of himself, he went too far. At lunch Romulus would climb the eighty-foot service ladder to the roof, then jump off, smacking the lawn face-first like raw meat hitting linoleum. At first the other children were horrified, and even Abigail refused to watch. But once it was clear Romulus could somehow avoid injury, everyone grew more fascinated with each display. After a few trial jumps Romulus modified his leaps into artistic dives, his body compressing like a spring when he hit the ground. Bobby did not understand the charm, and stood apart from the other children.

Some of the other boys set out to imitate Romulus, but either came to their senses halfway up the ladder or were stopped by a supervising teacher. No one found the nerve to jump.

After weeks of watching Romulus bask in the crowd’s admiration—and more importantly, Abigail’s—Bobby decided the only way to beat Romulus was to match him stunt-for-stunt. He had no thought of injury; his classmates were simply intimidated by a drop that looked worse than it actually was.

At the end of the school day he climbed the service ladder to the roof, spread his arms like airplane wings, bent his thick knees like a diver. Romulus, who had been talking with Abigail and some of her friends below, looked up; his jaw hung open and he shook his head weakly. “Don’t do it,” he pleaded, but it was too late. Bobby’s feet left the ledge and he plunged like a meteorite. Halfway down he realized the depth of his mistake and tried to straighten out, hoping he could avoid serious injury if he landed just right and bent his knees. When he hit the ground he felt his femurs smash up through his hips like pistons, the bones crunching together on impact.

He slowly became aware of a terrible stabbing pain in his pelvis. He could not move his legs; they had turned to pudding inside. He tried to call for help but could only spit out a few pained wheezes. A huge circle of children gathered around him, blocking out the afternoon sun.

A teacher spotted him and called for an ambulance. The paramedics stabilized his neck and back, strapped him to a gurney. As they loaded him into the ambulance, he saw Abigail Wheat in Romulus’ arms, watching him and crying. His eyes remained fixed on them until the paramedics closed the doors, and as the siren began to wail he wanted to close his eyes and die.

When Bobby woke, numb from painkillers, his doctor broke the news. He’d been lucky; had he not turned at the last second his spinal cord might have snapped, paralyzing him, or even rendering him unable to breathe on his own. His hip joints were mangled, his legs crushed; the surgeons nearly had to amputate. At least he could still have an independent and somewhat normal life, confined to a wheelchair instead of a respirator. In time—here the doctor smiled and patted his shoulder—with extensive therapy, he might even regain partial use of his legs. Had he been able to lift himself out of bed, he would have dashed his brains out on the plaster wall or strangled himself with the I-V line.

On his third day in the hospital, his parents brought him a grocery bag full of get-well cards from his classmates and teachers. Though he refused to look inside, his mother insisted he lay still while she read them aloud. When she pulled out Romulus Wayne’s card and read his name, he tore the card from her grasp, tore it to shreds, and cast it into the wastebasket beside his bed. “I don’t ever want to hear his name again,” Bobby said, then collapsed back into bed, exhausted from the effort.

A few days later Romulus Wayne came to visit. Bobby was half-asleep when he thought he heard Jackson Wayne’s steely baritone in the hall, saying softly, “I’ll wait out here.” He lifted his head to see.

Romulus was standing in the doorway, hands tucked in his pockets. “Hi, Bobby.”

Bobby felt his face redden. The thought of Romulus Wayne seeing him in a hospital bed was intolerable, and he pulled the thin blanket up over his shoulders.

Romulus stared down at his feet. “I’m sorry about what happened.”

“Fine. You’re sorry.”

Romulus took two nervous steps into the room, but did not look up. “It was kind of my fault,” he said. “I was showing off, being stupid.”

Bobby propped himself up on his elbows. “Yeah.”

Finally Romulus’ eyes met Bobby’s. “Come on. Don’t be like that.” He seemed to find his courage, creeping closer until he was right next to Bobby. He reached across the bedside table and held out his open hand. “No hard feelings?”

Romulus’ sincerity was disarming, and for an instant Bobby gave in. He reached up weakly and shook Romulus’ hand.

“Thanks,” Romulus said. His somber face brightened a bit. “I think Abigail’s planning on coming up as soon as her mom can drive her.” He stopped and said nothing for a minute, the corner of his mouth angling into a barely perceptible smile, and Bobby knew he was thinking of her.

Bobby’s body tensed, moisture welling behind his eyes. He wanted to turn away, bury his face in the pillow so Romulus would not have the satisfaction of seeing him cry. He grabbed the pink water cup from the bedside table and hurled it. Romulus ducked, sprinkled by a few droplets trailing in the cup’s wake.

“What was that for?” Romulus said, his voice cracking.

“Just go,” Bobby spat. “Go back to that redheaded bitch and leave me alone!” He threw a half-empty pudding cup across the room, spattering the wall with vanilla scum.

“I’m sorry,” Romulus said weakly. Bobby reached for the half-filled urine bottle on the table, but Romulus had already gone. He pulled the pillow from under his head and pressed it over his face; he was determined not to cry, but if he did no one else was going to hear.

When Bobby came home the house seemed larger, more cavernous, though the only changes were the ramp out front, the metal grips on the wall by the toilet and in the bathtub. His room was alien to him, his bed fitted with rails to help him get out of bed in the morning. For the next few months he recuperated in bed, bored to the point of despair. Physical therapy was an even greater torture: three times a week he had to hold himself upright using a pair of metal rails, then slowly transfer his weight to his feet, an ounce at a time. This alone required all his strength and left him dripping with sweat, his shoulders and triceps aching. But when he relaxed his arms he felt searing pain in his knees and hips, and more than once the nurses had to catch him before he collapsed. He learned to tolerate the pain for a few seconds at a time, but his legs were never strong enough to support him.

When Bobby was well enough he transferred to a school in another district, with better accessibility and programs for disabled children. He did not object. He would have gone anywhere, as long as it took him far from Romulus Wayne.

3

Despite his mother constantly pleading him to get some fresh air, Bobby rarely left the house except to go to school, and he never looked out the window for fear of seeing Romulus and Abigail walking hand-in-hand down the street. He still thought of them each morning as he heaved himself out of bed into his wheelchair or struggled to dress himself. Even his dreams were haunted; each night in his first moments of sleep he looked down at the eighty-foot drop, saw Abigail in Romulus’ arms. He felt his feet leave the roof, the rush of air in his face, the impact as he hit the ground like a dead fish flopped onto a cutting board. When he looked up, Romulus and Abigail were standing over him, hand- in-hand, pity in their faces.

For three years he had these dreams. But eventually they came less frequently, until he no longer dreaded sleep. He still heard their names on occasion; it was a small town, and there was no way of avoiding them completely. His aunt was a friend of Jackson Wayne, and occasionally gossiped with Bobby’s mother about goings-on in the neighborhood. “Such a cute couple,” she said of them, though his mother quickly shushed her and changed the subject.

But Bobby no longer cared. Every evening after he hoisted himself into bed he would lie still and

concentrate on sliding his legs across the linen, as if his will alone could reinforce the shattered bone and make his legs move again. The pain had mostly disappeared, except on humid days, but he could still only manage a few jerky twitches. After the accident his doctors told him it might be years before he could stand upright. It seemed terribly unfair, especially having to hoist himself onto the toilet or into bed with the aid of metal rails. But his arms were strong and well-defined from propelling his wheelchair, and sometimes he distracted himself by flexing in the mirror, watching his biceps bulge to hard, sharp peaks.

His new school was only a minor comfort; he was far from the old junior high and all its demons, but he seldom spoke to the other children. The long commute made friendships difficult; worse, they had long since made peace with their conditions, and rarely complained. He felt strangely separate, as if he lacked the awareness necessary to fit into their circles.

The Indestructible Man

The Indestructible Man