- Home

- Jablonsky, William

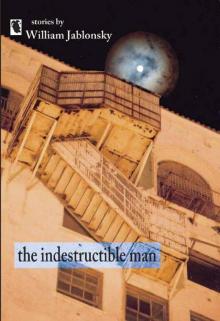

The Indestructible Man Page 10

The Indestructible Man Read online

Page 10

“Mrs. Barczak tells me you’re very involved with some kind of game, maybe more than you should be.”

“It isn’t a game,” Adam says plainly.

“Adam,” Miss Martha says, leaning closer to him, “Sometimes our imagination runs away with us, and it’s hard to tell what’s real and what isn’t. It happens to grown-ups, too.”

“But this isn’t my imagination,” he says. “This could be important.”

Miss Martha smiles sweetly. “So you’ve been talking to aliens from outer space?”

Adam looks at me, then his mother. “Tell her the truth, dear,” Margot says, smiling tensely. She wants him to say he was just pretending so we can go home. But I know he won’t.

“Yes,” Adam says.

Miss Martha’s smile disappears for an instant. “But Adam,” she says. “You’re a very bright young man. You know aliens aren’t real.”

He seems astonished by her ignorance. “How can you say that?”

“Adam,” Margot starts to warn him, but Miss Martha urges her to let him speak.

Even before Miss Martha answers I know she is hopelessly out of her depth; he has absorbed information from dozens of astronomy guides and PBS documentaries, and we have had these debates before.

“Well, for starters,” she says, “we’ve never seen any.”

Adam sighs, looks at her as if she is a dense child. “We’ve never seen black holes, either, but we know they’re real. Besides, there are millions of stars just like the sun, and we know some have planets. We know. Some of them could be like Earth.”

Miss Martha’s lips curl inward and she jots a few notes in her pad, regrouping. “But Adam,” she begins again, “if you really are talking to aliens, why are you the only one who can hear them?”

He rubs his chin, takes a deep breath. “I kinda wondered about that too,” he says. “I guess I was the only one listening. The big radio telescopes can pick up a lot more, but they usually look for signals far out in space. This one’s close.”

I try to stifle a grin; if my son is a lunatic, he is a smart one.

Miss Martha crosses off a note in her pad. “Sounds like a big discovery. Any reason you haven’t shared it yet? With someone besides your classmates, that is.”

He smiles proudly. “I’ve written down all the frequencies where I heard them. I’m going to call somebody when I figure out where their ship is.”

“Adam, stop it,” Margot says, suppressing tears. Her face is pasty white; her thin, spidery fingers clutch the upholstery. “You can’t really believe all this.” She glares at me as if to say, This is all your fault.

“But I can prove it,” he says. He pulls his tape recorder from his pocket and presses the play button. For a few seconds, I hear a conversation, the ‘aliens’ trying to teach Adam their language. The voice is familiar, but there are others too, their words made up of sounds I have never heard from a human throat.

With a trembling hand Margot snatches the tape recorder and shuts it off. “This is ridiculous,” she says.

He glances at me, about to ask for backup, and I try to think of some way to explain this that will not land me in court. Margot would love an excuse to “revisit” our custody agreement, an unspoken threat she carries like a gun.

Miss Martha comes to the rescue. “Adam, you haven’t really made friends here yet, have you?”

Adam rolls his eyes and sighs deeply. “I guess not. But what’s that got to do with the aliens?”

“It can be hard not having someone to talk to. With your parents split up, it must be even harder. Don’t you ever feel lonely or sad?”

He shakes his head sadly. “You’re not even listening to me. You think I’m just making this up, like an imaginary friend.”

“Adam,” Margot says sternly.

“It’s all right,” Miss Martha says. “If you don’t mind,” she says, turning to Margot, “I’d like to talk to Adam alone for a few minutes.” She gestures toward the door.

“You see how far you’ve let this go?” Margot whispers as we step out into the hall and Miss Martha closes the door behind us. “Why didn’t you stop it? Guilt?”

“Go to hell,” I whisper back. I kneel in front of the door, press my ear to the wood.

“What do you think you’re doing?” Margot says.

“What does it look like?” I say, and wave her over.

“Oh, for God’s sake,” Margot says, then kneels down next to me.

We make out only muted pieces of conversation—Miss Martha’s saccharine voice asking him about the separation, his new house and school, telling him these things happen and can be hard to deal with. Though we can barely hear him, Adam’s tone seems to grow angrier with each question; he will not be converted. We scramble back to our plastic chairs when we hear footsteps shuffling toward the door.

Miss Martha’s verdict is no surprise: Adam is depressed over the divorce and his new school, believes his ‘aliens’ are the only ones he can turn to for meaningful communication. Had I not heard whatever I heard, her explanation would seem perfectly reasonable. Margot reminds me that I am to blame; I have hurt Adam by letting him continue this game so long.

He is to meet with Miss Martha once a week for the next few months; in the meantime she encourages us to nudge him into social activities—Little League, soccer, Boy Scouts. Margot gives her word and goes a step further, promising to forbid Adam any sci-fi books or comics. Miss Martha urges her not to take such drastic measures, but Margot has already made up her mind.

“I want that radio gone by Friday evening,” she says as we leave. I wave her off and walk away; even if I tell her the truth Adam will still have to visit Miss Martha, will still have Mrs. Barczak looking over his shoulder, will still be pulled out of the house to play Little League or some other thing he despises.

Adam is unfazed when I give him the news. “I’ll show her,” he says. “She’ll understand if she just listens.”

“Are you sure?”

“You did.”

When Margot brings him to the door I tell her the radio is already in the trash. Once she leaves Adam hurries to his room to finish his work. For the rest of the weekend he pores over his planetary charts, searches the night sky with his telescope, tries to get his aliens to communicate their position. Late Saturday night I stand outside his door and hear him speaking whole alien sentences into the walkie-talkie; he no longer stumbles over the words, and seems to have developed an accent. I do not interrupt; it is a kind of goodbye.

Margot arrives at four on Sunday, brushing past me on her way in. “Adam?” she calls.

“Just a sec,” he says, and we both hear rustling from his room.

She sighs and walks around me as if I am a tree or lamppost.

I follow her back to his room; he is frantically poring over frequencies, looking over his shoulder every few seconds. He nearly falls out of his chair when he sees her. “Mom, this is too important,” he says. “Don’t make me take it apart.”

“It’s for your own good, honey,” she says.

“Wait,” he says, holding the earpiece out for her. “It’s the wrong time of day, but if you just wait a little while….”

“I don’t have time for this,” Margot says.

Adam gets up out of his chair and stands in front of the radio’s exposed wiry insides. “Dad, don’t let her do it. You heard them too—tell her.”

Margot looks at me, raises a penciled-in eyebrow. “Heard what?” she says.

I want to tell her he is not just imagining this, shove the earphone into her ear and make her listen for herself. But it is still too early, and I doubt she would listen anyway.

“Nothing,” I finally say. “I guess I just let it go too far.”

“I guess so,” she says.

Adam’s mouth drops open. “But Dad…” A few years from now he will understand all this, but for now I have betrayed him. He runs into the living room and crumples into a ball on the couch, as Margot tears apart the de

licate wire bridges between the radio and walkie-talkie, rips the antenna connection out of the wall, even dismantles his telescope. “Are you going to help me?” she asks. I grab the walkie-talkie and some stray wiring, and follow her out back, carrying a mass of plastic and wire. We drop the whole mess into the garbage can, then quickly cover it over with the lid. I lean against the can, grasping the lid on each side, my fingertips denting the aluminum.

For a minute her taut features soften, and she hesitantly touches my arm. “We’re doing the right thing. We can’t let him get so caught up in this silly game.”

I shake my head. “He’ll never trust me again.”

“He’ll forgive us eventually,” she says.

“Not likely,” I say, and head back to the house.

When Adam is finished packing he races out the door ahead of her without saying goodbye. I stand on the porch and watch them drive away, Adam crouched low in his seat so I cannot see him.

Once they are out of sight I go back inside to straighten up, gathering stray wires from his desk and the floor where they fell. When I make his bed my hand crinkles a small stack of paper stuffed under the pillow; I pull it out to find complete charts of all the connections between his radio and the other components, a list of frequencies and times he’s made contact, a brief glossary of alien vocabulary. On top of the stack is a yellow sticky-note, scrawled in blue pencil: You know what to do.

I sneak back to the trash bin as if being spied on, and dig out the disemboweled husk of the radio, the walkie-talkie half-caked with spent coffee grounds. Arms full, I carry it back to the tool shed and dig out my needle-nose pliers, soldering iron, and screwdrivers. I shuffle through the schematics until I find the right ones and tack them up, wallpapering the shed. Adam’s drawings are faint and complicated, in places muddled by jumbled notes and eraser marks. It will take me a week just to figure out where to put all the mangled parts, longer to restore all the connections. But the shed is private and safe, hidden behind a pair of evergreens in the backyard; Margot may even have forgotten it exists.

I set to work, and remind myself to ask Adam the alien word for hello.

The Space Between Earth And Moon

Henry has been somewhat unhinged since Cora’s untimely death of cancer. Because he is our friend we accept this and have learned to accommodate him, even in moments when his eyes become bulbous like a goldfish’s and his fingertips tap long convoluted rhythms onto tabletops. Very little he does surprises us. Then, during a beer-and-poker session on his patio, he says he intends to travel to the moon. We try to coax his thoughts in other directions, and failing that, to drown them in bottle after bottle. Finally he excuses himself and shuffles across the grass to the little creek behind his house, steps into a flatbottom fishing boat with no oars or motor, sits there for a good hour staring at the moon, low on the horizon. We watch him, concerned but unafraid, until he unties the boat and lets the current take him, spinning toward the mouth of the creek and into the river, under the low-hanging moon. He makes no move to steer himself, merely sits head in hands watching the river gape before him. We follow him along the gravelly mud of the riverbank as far as we can, but the current’s stamina is greater than ours and we can only watch the swift water sweep him away.

Three hours later, when we spot his silhouette from the highway bridge, we are grimy and drenched with sweat, our shoes caked with thick gray muck from the riverbank. The flatbottom has beached itself on a sandbar near the bridge, Henry sitting motionless in the center, staring past us, past the road, into the full moon rising in the purple sky. When we hike up our trouser legs and wade out to retrieve him he says nothing, does not take his eyes from the moon’s glow even when we carry him to the truck and lay him in back, holding his legs and arms to prevent him from leaping onto the highway on the way home. We swear never to mention the incident to outsiders or bring it up to Henry.

But we have learned to embrace his eccentricities, or at least to humor them. So when he announces his intention to build a catapult large enough to send him to the moon we listen closely, nod as if we understand, even suggest approaches when asked for input. He stays up well into the night reading schematics, penciling blueprints onto legal pads, studying astronomy journals from the public library, shows up at the barbershop and supermarket with darkened hollow eyes and grayish skin, lips stretched into a taut, satisfied smile. His crops are already suffering from lack of care, the cornstalks yellow and papery, his tomato plants wilted and brown, the flowers in his greenhouse withering.

A few days after the boat incident the Gazette’s police beat section begins to run stories of break-ins all over town. A pair of wooden shafts the length of telephone poles and almost a half-ton of boards of varying sizes, from two-by-fours to twelve-by- twenty-fours, are spirited away from Bill Haan’s lumberyard in the middle of the night. Midwestern Steel Fabrication reports metal rings, a length of steel cable, a pair of fifty-gallon drums, and a great many steel spikes and bolts missing from its inventory lot. In Ray’s Junkyard a battered Volkswagen is cannibalized for parts, its passenger seat ripped from the vehicle, all right under the vigilant nose of Booch, Ray’s German shepherd. Sheriff Tomkins’ profile of the thief suggests that the robberies might well be the work of a professional, someone with the ability to appear and disappear at will; no normal person could have climbed over Ray’s chain-link fence without being mauled. He advises us to watch closely but to keep our distance, as anyone with the skills to slip past Booch and conduct such daring thefts must be considered very dangerous.

Everyone knows Henry is behind the break-ins. We even help him from time to time with larger items he cannot transport alone. We climb rusty fences, hurriedly gather up components at Henry’s direction, load them into our trucks and station wagons, and speed away into darkness before anyone knows we have been there. The price is sometimes high; the rusty links of old fences leave our fingers and forearms shredded and bleeding, and when we walk into the emergency room for sutures and tetanus shots the doctors and nurses know what mischief is up. But they know us, and they stitch us up without chide or lecture. It is a price we are glad to pay; Henry is grieving, and if he wants to try to build an impossible contraption to send him to the moon, we will help him.

Eventually most of the shop owners catch on. Several, including Bill Hahn, begin to leave their gates open to allow Henry easy access, sometimes even leave piles of throwaway raw materials with a note that says, “Help yourself, Henry.” Sheriff Tomkins knows it too, but as long as Henry limits himself to surplus or cast-off items Tomkins allows him to continue undisturbed.

From time to time we ask for a look at the device, but Henry shakes his head. “Not ’til it’s finished,” he says. For the moment we accept this condition. Even if it is impossible, if he eventually fails or gives up, it is the most interest he has shown in anything since Cora’s passing, and we would be saddened if our prying forced him to abandon it.

Once the robberies have ended and Henry is satiated he calls less frequently, shows little interest in card games or fishing trips, often even fails to answer the door when we come unannounced. At the supermarket he avoids us, briefly nodding and tipping his baseball cap to our wives before disappearing, quick and silent, down one aisle or other. After a few weeks of this we grow concerned, drive up his gravel road in the faint early morning light. We wander around back to peer in his windows to see if he is sprawled dead in the breezeway or the bedroom, prepared to be hit by the rotten-milk smell or to see him crumpled blue-skinned in a corner. But we do not find him. We creep back even farther through the dewy grass, silently so as not to startle Henry if he is there. In the weedy field behind the house we spot the orange glow of his electric lantern, half-hidden behind a patch of crabgrass, the silhouette of steel drums, stacks of heavy lumber.

We inch closer, trying to remain hidden behind the protective wall of blue spruces that separates Henry’s backyard from the field, until we are close enough to see Henry sitting cro

ss-legged in the unplowed dirt and weeds, to hear his occasional grunts and coughs. Around him the lumber and steel and other plunder lie sprawled in the grass, carefully arranged, more like the fossilized remains of a mammoth than unassembled machine parts. He rises painfully and, rubbing the small of his back, looks over the components spread out around him. He seems to straighten up with pride, and we smile, grateful that he is at least happy. Then he shuffles toward the house and we run through the damp grass, tear away down the gravel road before he steps through his back door. If we have in any way revealed ourselves, he does not say. We tell only our wives and girlfriends about what we have seen, certain Henry’s privacy will remain intact.

It does not, of course. Within a day or two everyone at the market or the barbershop seems to know Henry is building something. We glare accusingly at one another over bar tables or across shopping carts, for we cannot be certain whose slip of the tongue betrayed Henry. There are many stories, though the exact details seem to grow more muddled with each telling. Some say he is building a rocket-ship, others a cannon. A few claim he is building a gallows to hang himself. This we find silly and even amusing. If Henry wished to commit suicide he could find simpler methods. We decide that, while Henry’s pursuit is not normal, it is still a harmless distraction and the worst that can come of it is wasted sweat and lost sleep.

The Indestructible Man

The Indestructible Man